I want a teach a neural network how to play Tetris.

source code: https://github.com/opyate/neuro-evolved-tetris

video: https://youtu.be/rji6zOQgJZs

What are the possible approaches?

A supervised learning approach could be that I record a Tetris world champion playing lots and lots of games, then create a large labelled dataset, then train a model on said dataset. However, that’s a lot of work, and the model might generalise to play exactly like that world champion and potentially miss out on novel Tetris techniques and play styles.

A reinforcement learning (RL) approach could be that the AI agent learns by playing the game, receiving rewards for scoring and staying alive longer, and penalties for filling up the Tetris grid without clearing lines. It adjusts its actions (move a piece left or right) to maximise its score. That involves defining a policy (which is a strategy that maximizes its cumulative rewards over time) and a corresponding reward function to provide feedback for adjusting the policy. In fact, RL works quite well for game playing and robotics!

But, I want to try something a bit different, like genetic algorithms ᵃ. Specifically, neuroevolution.

Like reinforcement learning, neuroevolution allows an AI to learn through interaction with an environment, but instead of directly adjusting actions, neuroevolution focuses on evolving the neural network. Different neural networks with varying weights ᵇ are tested in the game, and the ones that achieve higher scores are selected and “bred” to create new generations of better-performing Tetris players.

Crucially, this approach will differ from the other approaches in that it doesn’t use backpropagation to update the network weights and biases (during which the network uses gradient descent to calculate the gradient of the error with respect to each weight and bias, with the gradient indicating the direction and magnitude of change needed to reduce the error). If you look at the code, you’ll only see the forward pass implemented.

So, neuroevolution it is!

Overview of experiment

Here are some high level steps that describes the simulation.

- spawn thousands of bots from the simulation runner

- each bot contains

- a brain, aka a PyTorch network, which has

- 10x10 inputs which represents the Tetris grid

- a hidden layer

- 7 outputs which represents the possible player moves (left, right, etc)

- random initial weights

- a Tetris engine, which

- maintains the internal game state

- allows 7 possible moves to modify said game state

- a brain, aka a PyTorch network, which has

- the simulation loop now starts, and every bot predicts their next move

- after each bot made their move, they get fitness points

- for staying alive,

- for scoring (i.e. clearing lines on the Tetris grid)

- after each bot made their move, they might also be in a game over state

- after all bots reach game over, they evolve

- evolution step 1: parents are chosen based on a weighted selection

- evolution step 2: the parents reproduce via crossover, to produce a child

- evolution step 3: the child is slightly mutated

- the children becomes the brains for the next cohort of bots, with a fresh game state

- the simulation loops again

The PyTorch network

I use PyTorch to create a network with 10x10 inputs to represent the Tetris grid ᶜ, and 7 outputs to represent the possible moves, which are:

- up

- down

- left

- right

- rotate clockwise

- rotate counter clockwise

- no operation (do nothing)

Given any grid state (e.g. an empty grid with a starting piece at the top, or a mid-game grid with some stacks at the bottom), the model will run a classification task, i.e. which is the best move to make given the current state.

The Tetris Engine

I built a Tetris engine from scratch that was completely decoupled from any game ticks and rendering logic. This allows me to run a simulation as fast as my CPU ᵈ cores will allow, thereby not having to wait for one game tick every 16ms (if we assume 60FPS)

Scoring is standard Tetris scoring and I even implemented rotation using the recommended SRS (Super Rotation System) strategy, which allows for wall kicks.

The engine also detects if the bot plays many repeat moves (that aren’t up or down), upon which is forces game over.

Weighted selection

Our weighted selection function uses a relay-race technique for giving a fair shot to all members of a population, while still increasing the chances of selection for those with higher fitness scores.

It works like this:

- imagine a relay race, where each bot runs a distance tied to its fitness

- the higher the fitness, the farther they run

- pick a random starting line (so, a random distance to the finish line)

- the race begins with the first bot, and it runs a distance equal to its normalised fitness score

- loop for every bot

- the race ends when a bot cross the finish line

- that bot is selected as a parent

In essence, every bot has a shot at crossing the finish line, but those with higher fitness can run longer distances, thus have a better chance of being selected to be a parent.

Alternatively, we could just select the bots with the highest fitness each time, but this decreases the amount of variety in the system, as lower-fitness bots might still have interesting play strategies up their sleeves.

Evolution

Crossover

This is the reproduction part of evolution. We start with a blank child network, then for every weight in the network, select either parent A or parent B’s weight as determined by a virtual coin flip.

Mutation

This mimics real-world genetic mutations, which typically introduce minor changes rather than entirely new traits.

We define a very small mutation rate (0.01) which means that only 1% of the weights in the child’s network will be changed slightly by a small Gaussian noise.

Results

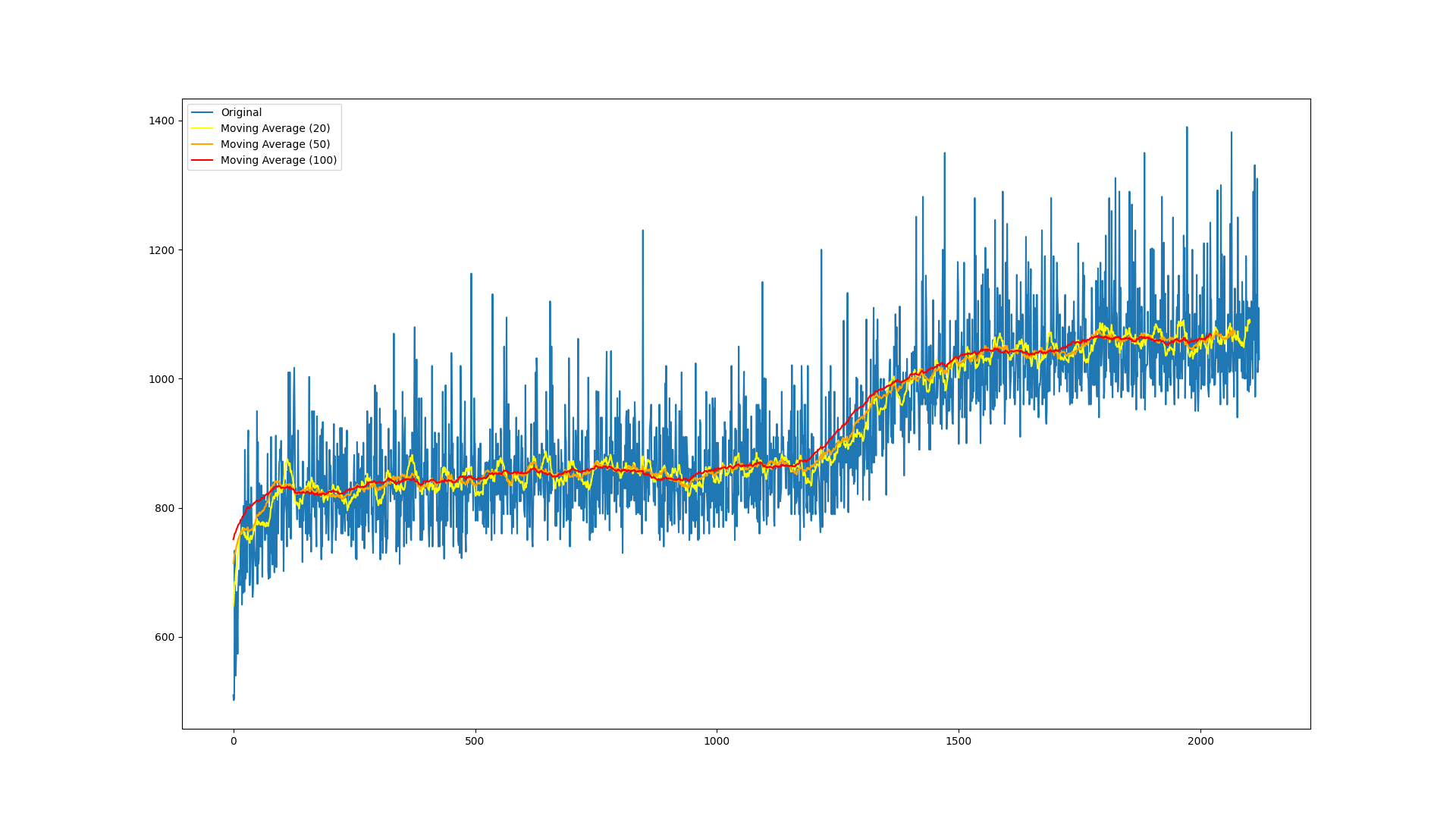

After 2,000 rounds of Tetris, the bots are clearly on an upward trajectory and increasing their fitness.

The variance in the mean fitness plot can be explained by the weighted selection algorithm, in that we still sometimes pick less fit parents to reproduce, with the expectation that the mean fitness sometimes takes a hit. However, the moving average shows a clear upward trend in fitness.

Other things to try

Try alternate fitness allocation

At the moment, fitness is

- increased by 1 for every tick of staying alive

- BUT increased by 100/300/500/800 (depending on number of lines cleared) for scoring in the game.

A bot might score by chance, but not necessarily have learnt a strategy for staying alive longer, which gives it an outsized benefit in the simulation.

Try other weighted selection algorithms

- Roulette Wheel Selection (Lipowski, 2011): Each individual is assigned a slice of a roulette wheel proportional to its fitness. A random “spin” of the wheel determines which individual is selected.

- Rank-Based Selection (Whitley, D. 1989): Individuals are ranked based on their fitness, and selection probability is assigned based on rank rather than absolute fitness values.

- Tournament Selection (Goldberg, D. E., & Deb, K., 1991): A subset of individuals is randomly chosen, and the individual with the highest fitness within that subset is selected.

- Elitism (p101 of De Jong, K. A., 1975): A certain number of the best individuals from the previous generation are directly copied into the next generation.

Conclusion

At the time of writing this, I’m not yet seeing a bot which is clearly good at Tetris, so I’ll keep the simulation running, and revisit this post with an update.

Meanwhile, please try the experiment yourself, make modifications, and let me know what you find!

Footnotes

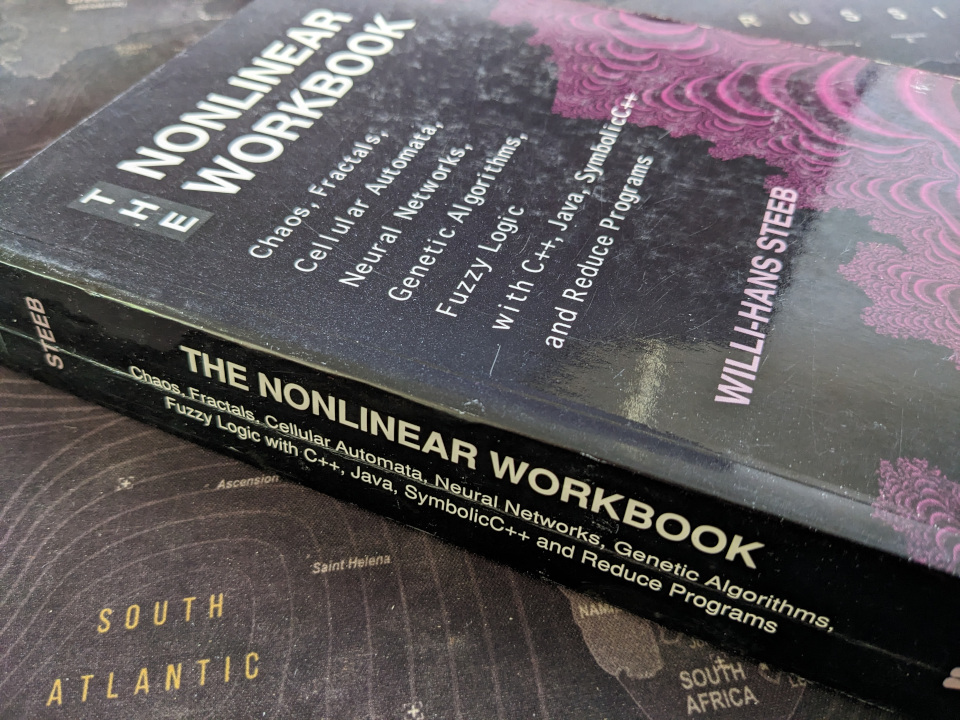

a. Genetic Algorithms (GAs) are a class of algorithms inspired by biological evolution. They operate on a population of candidate models (individuals), using selection (usually the fittest), crossover (recombination, or reproduction by two parent models), and mutation to iteratively improve their fitness for a given task. A battered copy of one of my uni textbooks from 1999 discusses genetic algorithms, and was one of the inspirations for this post! (That crack in the spine aligns with chapter 11, Neural Networks ;-)

b. More elaborate neuro-evolutionary techniques also modify the network’s topology (see NEAT, HyperNEAT, ES-HyperNEAT) and even hyperparameters (CoDeepNEAT) but we’re keeping things simple for now.

c. Standard Tetris has a 20x10 grid, but most of it is open space at the start of a game, so I halve it to get to learning quicker and make the underlying neural network smaller.

d. I used CPU instead of GPU, because the networks were quite small and any gains in GPU acceleration would be impacted by copying data to and from the GPU. This opens the experiment up to others to tinker with. Note that evolutionary processes can sometimes be slow to converge to optimal solutions compared to gradient-based methods, so grab a cup of tea!